Many people in Guam enjoy hiking–walking outside in a natural environment, often following a pre-charted path known as a hiking trail.

However, some hikes involve more challenging terrain and other conditions for participants. Some examples of the different terrain include hills, mountains and rivers.

Hiking safety is important, and I believe Guam’s residents should be more aware of the precautions before going on a hike. The activity turns into a more daunting task without adhering to precautionary measures that have the potential to reduce harm towards participants.

Bodily harms

First, there are certain medical conditions associated with hiking such as Lyme disease and Leptospirosis.

Lyme disease, which has up to 300,000 reported cases annually in the United States, is contracted by a bite from an infected tick.[1] Meanwhile, Leptospirosis is caused by close contact with a contaminated water or soil source.[2] The bacterial species, Leptospira, can be found in the urine of infected animals and deposited to water or soil sources. The bacteria can be viable in a source for weeks or even months. The disease itself thrives in tropical climates, which is a cause for concern to local hikers.

Knowledge of Leptospirosis is important for hikers in Guam because of its reported cases on some hiking trails. Two prominent, reported cases of a Leptospirosis outbreak occurred in 2000, followed by another in 2014.

After the 2014 outbreak, the Pacific Daily News, in collaboration with the Guam Department of Public Health and Social Services, issued a warning and provided information from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s website about the disease.

The Guam DPHSS also determined that the disease could be contracted from southern rivers in Guam. Additionally, another part of the release was specifically geared towards the local population: “hikers should avoid swimming in Guam’s rivers during the rainy season or, if they do swim, avoid swallowing water or getting water in their eyes or nose.”

Other risks

Second, there are other risk factors involved with hiking in Guam—risks related to the level of difficulty of some hiking trails.

Guam Boonie Stompers, Inc., a local nonprofit organization, organizes and participates in hikes on a regular basis. Their namesake derives from the term “boonie stomp” which is local slang for hiking trail. Those people who go on boonie stomps, in turn, refer to themselves as “boonie stompers.”

The organization is well known for its Saturday morning hikes. It also does its best ensure hiking safety through precautionary measures. Although there is a fee assessed for each eligible person participating on a hike, the organization ensures that a guide who is knowledgeable of the given trail accompanies hiking groups.

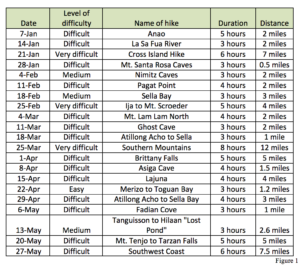

In the table below, Figure 1, I compiled information from the Guam Boonie Stompers, Inc. articles featured in the Pacific Daily News and on its official Facebook page for the January to May 2017 hiking schedule.

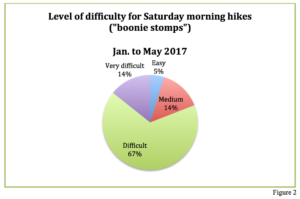

The GBS have a hike rating system of easy to very difficult. I have assigned numeric values of one to four (one equals an easy level of difficulty) in order to make a pie chart, which provides a visual representation to further categorize the hikes.

The pie chart, Figure 2, highlights the fact that out of the 21 hikes in Figure 1, 67 percent of them are ranked as difficult. One hike that is classified as difficult involves navigating through caves and swimming which is the Mt. Santa Rosa Caves hike.

The need for outreach

Because of the variety of terrains and bodily harms hikers can be exposed to on these trails, I think that there should be more public outreach such as PSAs and other campaigns. I do not think that it is enough to tell people to wear comfortable clothing and shoes, bring water and sunscreen, etc.

I believe there would be a significant impact on the local community if there were positive but also preventive media and campaigns to focus on the issue of hiking safety.

Because of Guam’s tropical marine climate, which has fairly consistent temperatures year-round, hikers will be exposed to not only different types of terrain but also the possibility of other bodily harm such as dehydration and fatigue.

Hikers also are prone to blisters and skin rashes[3], to name a couple of other bodily harms.

Such bodily harm could contribute to hikers getting lost and having to be found via search and rescue operations (when unaccompanied by a guide who is knowledgeable about the trail(s), generally).

A recent PSA posted on YouTube entitled USNH Guam – HIKING SAFETY: Leptospirosis[4] provides information such as identifying the illness and prevention methods. Two U.S. Navy sailors stress the importance of Leptospirosis awareness and prevention as they walk outdoors to Tarzan Falls.

The video’s conclusion gives viewers a brief overview of the standard attire and supplies, which are emphasized by organizations such as the Guam Boonie Stompers, Inc.

The PSA serves as an example of how public outreach can occur in the future by other public and private companies.

Experts weigh in on the issue of hiking safety

On the other hand, some experts on outdoor activities provided insight based on personal experiences as well as studies involving hiking safety.

Marcus Bailie, head of inspection at Adventure Activities Licensing Service says, “The secret of survival is to ensure that no single error causes a catastrophe.”[5]

Bailie, who has more than 30 years of experience involving adventure activities, discusses errors that commonly occur during those activities. He argues that mechanical errors during outdoor activities are not as common as human ones. An example of a human error that could result in an accident is the myth of instructor infallibility.

Jimmy Roark, a former hike leader of Guam Boonie Stompers Inc., shared information about hiking safety and the organization’s classification system. The system, in particular, determines a hike’s level of difficulty.

Currently, Roark is in charge of the official GBS Facebook page.

According to Roark, most of the people that are unprepared for hikes in Guam are visitors/tourists. He says that these visitors “want to try out a bit of adventure and often they do not know the dangers of hiking.”

However, his perspective on local residents and their knowledge of hiking safety was that they either come prepared or do not participate in the hikes due to awareness of the possible risks.

The GBS’s classification system is determined by the following factors: length (in miles), type of trails, time spent on the trail, and required technical skills.

If I had not spoken to Roark or another member of the organization, I would be unaware of the reasons behind the classification system and how hiking safety is practiced locally, especially by the organization.

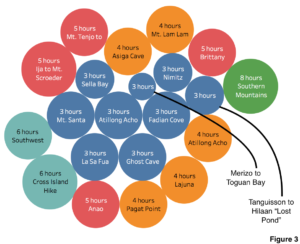

As shown by Figure 3, different colors and sizes of the circles conceptualize the duration (in hours) of GBS hikes from January to May 2017. I think that it would be more effective to have these types of data visualizations to increase awareness of information that is provided to the public.

Since the GBS and other agencies have their own official Facebook pages and websites, it might be helpful to post data visualization instead of plain text lists as their posts. In regard to GBS, they update the page’s “General Description” section to show the hiking schedule for the upcoming 3-4 months.

Roark did not specifically mention how frequently injuries, illnesses, or search and rescue occurred. However, he does say that on every hike, some people do not comprehend the warnings, but they usually recover.

In one instance, he witnessed an experienced hiker tripping, falling, and breaking their arm.

Speaking to Roark further reinforced the concept of responsibility not only being valid on the institutional level but also the individual too.

Although there are no local statistics of research examining the effects of people misreading signs and not being adequately prepared for hikes, human error is a common occurrence for many outdoor activities.

Oftentimes, asking someone who misread or disregarded a posted sign results in excuses. But the truth is usually that their mind is “somewhere else” when it happens.[6]

It is also important to note that the GBS’s status as a nonprofit organization involves its collaboration with the Department of Parks and Recreation. GBS also cooperates with federal and local authorities when necessary.

A unique precautionary measure that GBS has in regard to hiking safety is ensuring that all participating hikers are accounted for from start to finish.

Roark explains that hike leaders are trained and the configuration of the group involves one leader at the front of the group and one at the back to discourage wandering. Participants also have their vehicle’s license plate information recorded by the leaders.

“So if there are any cars left at the end of the hike, we can know if it’s one of our hikers,” says Roark, “If it is, we go back and find the lost hiker.”

He also listed conditions that local hikers are exposed to in Guam. Those conditions included “heat/humidity, lack of drinking water on the trail, swordgrass and other plants, mud, slippery river rocks, and other hikers.”

Additionally, Figure 3 highlights the importance of being aware of the conditions people may be exposed to while hiking. Although some hikes are only a couple of hours long, others are more than five hours and require more careful planning to ensure hikers can safely complete the hike.

For example, not bringing enough water to drink could be fatal when coupled with the heat and humidity.

The next time I see the official signs on island for hiking or nature trails, it serves as a reminder that there is still room for improvement in regard to public awareness of information regarding hiking safety.

References

[1] The Center for Disease Control and Prevention defines “Lyme disease” on its “Prevent Lyme disease” page (https://www.cdc.gov/features/lymedisease/)

[2] The CDC also defines “Leptospirosis” on its page “Leptospirosis Risk in Outdoor Activities” https://www.cdc.gov/features/leptospirosis/

[3] Medical Risk of Wilderness Hiking by David R. Boulware, William W. Forgey and William J. Martin; see Table 2 (Incidence of Injuries and Illnesses, by Type of Hiker)

[4] A Joint Region Marianas Guam video production (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MtvFH2Hk0no).

[5] Human Error Accidents in Adventure Activities: Cause and prevention by Marcus Bailie (2010)

[6] Human Error Accidents in Adventure Activities: Cause and prevention by Marcus Bailie (2010)